Durango Bill's

Paleogeography (Historical Geology) Research

Dolores River, Anticline, and Canyon

Contour intervals

for all pictures are 100 feet. This three-picture sequence

traces the Dolores River in southwestern Colorado. The Dolores

has multiple examples illustrating “antecedence” – the process

where a river system establishes itself, and subsequent

tectonic uplifts change the original topography.

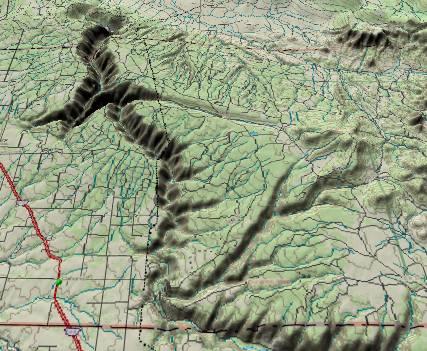

The first picture

shows the west branch of the Dolores River - including

tributaries flowing in from the northwest. Groundhog Reservoir

is just above the center of the picture. Groundhog Creek then

flows southeastward through the rising strata to join the West

Dolores River (which enters from the center of the right

edge). The flat surface of the Dakota Sandstone is underneath

Groundhog Reservoir, but slopes upward to climb more than

1,000 feet above the reservoir as you progress toward the

southeast.

The first picture

shows the west branch of the Dolores River - including

tributaries flowing in from the northwest. Groundhog Reservoir

is just above the center of the picture. Groundhog Creek then

flows southeastward through the rising strata to join the West

Dolores River (which enters from the center of the right

edge). The flat surface of the Dakota Sandstone is underneath

Groundhog Reservoir, but slopes upward to climb more than

1,000 feet above the reservoir as you progress toward the

southeast.

Obviously, Groundhog Creek established it course when “downhill” was toward the southeast. Subsequently, the terrain to the southeast was uplifted, but Groundhog Creek was able to cut down fast enough to maintain its original course.

About 6 miles to the south-southwest of Groundhog Creek, Cottonwood Creek illustrates an identical phenomenon. It also flows southeastward into rising strata/terrain and joins the West Dolores River just above the lower edge of the picture.

Even the West Dolores River itself ignores present topography. If you trace its path from where Groundhog Creek joins it (to the right and slightly below the center of the picture) to where it continues off the lower edge (left of center), its path is parallel to the smoothed contours. When the West Dolores River established its path, downhill was toward the southwest. Subsequently, uplift off the east and southeast edge of the picture altered the topography, but the West Dolores River was entrenched and simple dug down deeper into the rising terrain.

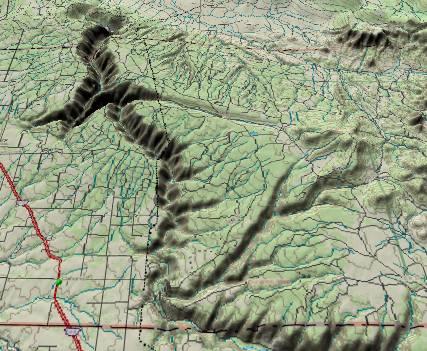

In the second picture

(view area is southwest of the first picture) the East Dolores

River enters from the right edge to join the West Dolores

River. The combination forms the main Dolores River which

continues southwestward and then westward to McPhee Reservoir.

Lost Canyon Creek flows from east to west along the bottom

edge, and joins the Dolores River at the south end of McPhee

Reservoir. (The small town of Dolores is just to the right of

the south end of McPhee Reservoir.) The Dolores River then

turns abruptly toward the northwest and enters Dolores Canyon

in the upper left quadrant. Dolores Canyon continues northward

across the anticline with the river forming a canyon over

2,000 feet deep.

In the second picture

(view area is southwest of the first picture) the East Dolores

River enters from the right edge to join the West Dolores

River. The combination forms the main Dolores River which

continues southwestward and then westward to McPhee Reservoir.

Lost Canyon Creek flows from east to west along the bottom

edge, and joins the Dolores River at the south end of McPhee

Reservoir. (The small town of Dolores is just to the right of

the south end of McPhee Reservoir.) The Dolores River then

turns abruptly toward the northwest and enters Dolores Canyon

in the upper left quadrant. Dolores Canyon continues northward

across the anticline with the river forming a canyon over

2,000 feet deep.

There is also a fault that runs from west-southwest to east-northeast through the center of McPhee Reservoir. Terrain to the southeast has been lifted several hundred feet above corresponding strata layers to the northwest.

Throughout the entire area shown in the picture, the Dolores River and its tributaries ignore current topography. Along the lower edge, Lost Canyon Creek is nearly parallel to current contours. The Dolores River from McPhee Reservoir to the northwest continues to flow parallel to the contour lines. If river systems followed today’s contours, they would flow southwestward toward the lower left corner. Obviously, some ancient river system obeyed an earlier topography, became entrenched, and continued these entrenched paths even though subsequent tectonic events changed the topography.

During the Eocene the ancestral San Juan River established a path across this area. It entered from the bottom edge (right of center) and exited at the top left. During the late Oligocene (and/or early Miocene) much of this area underwent regional uplift, which forced the San Juan River to find a new route further south in New Mexico. The upper portion of the current Dolores River (which was formerly just a tributary) was left as the sole owner of the old path from McPhee Reservoir downstream (up and left).

Lost Canyon Creek is another remnant of the ancestral San Juan drainage system. It was probably a local tributary to the ancestral San Juan.

This third picture

shows the continuation of the Dolores River where it cuts

through an anticline to form 2,000-ft. deep Dolores Canyon.

The ancestral San Juan River established this path some 50

million years ago. 50 million years ago, all drainage on the

western slope of the Rocky Mountains was from south to north

toward the Lake Uinta lowlands (Northeast Utah, Northwest

Colorado, and Southwest Wyoming), and the anticline did not

exist yet.

This third picture

shows the continuation of the Dolores River where it cuts

through an anticline to form 2,000-ft. deep Dolores Canyon.

The ancestral San Juan River established this path some 50

million years ago. 50 million years ago, all drainage on the

western slope of the Rocky Mountains was from south to north

toward the Lake Uinta lowlands (Northeast Utah, Northwest

Colorado, and Southwest Wyoming), and the anticline did not

exist yet.

Some 20 to 30 million years ago, renewed uplifts from the La Plata Mountains southward forced the San Juan to relocate further south into New Mexico, but the upper Dolores River which was formerly just a tributary, inherited the entire route. Since then, the anticline has been uplifted, but the Dolores was entrenched and simply dug deeper to form Dolores Canyon. The zigzag path within Dolores Canyon is probably a remnant of another ancestral river (the ancestral Chaco River) that joined the ancestral San Juan before it too was truncated some 20 to 30 million years ago.

Return to the Image Index Page

Web page generated via Sea Monkey's Composer HTML editor

within a Linux Cinnamon Mint 18 operating system.

(Goodbye Microsoft)

The first picture

shows the west branch of the Dolores River - including

tributaries flowing in from the northwest. Groundhog Reservoir

is just above the center of the picture. Groundhog Creek then

flows southeastward through the rising strata to join the West

Dolores River (which enters from the center of the right

edge). The flat surface of the Dakota Sandstone is underneath

Groundhog Reservoir, but slopes upward to climb more than

1,000 feet above the reservoir as you progress toward the

southeast.

The first picture

shows the west branch of the Dolores River - including

tributaries flowing in from the northwest. Groundhog Reservoir

is just above the center of the picture. Groundhog Creek then

flows southeastward through the rising strata to join the West

Dolores River (which enters from the center of the right

edge). The flat surface of the Dakota Sandstone is underneath

Groundhog Reservoir, but slopes upward to climb more than

1,000 feet above the reservoir as you progress toward the

southeast.Obviously, Groundhog Creek established it course when “downhill” was toward the southeast. Subsequently, the terrain to the southeast was uplifted, but Groundhog Creek was able to cut down fast enough to maintain its original course.

About 6 miles to the south-southwest of Groundhog Creek, Cottonwood Creek illustrates an identical phenomenon. It also flows southeastward into rising strata/terrain and joins the West Dolores River just above the lower edge of the picture.

Even the West Dolores River itself ignores present topography. If you trace its path from where Groundhog Creek joins it (to the right and slightly below the center of the picture) to where it continues off the lower edge (left of center), its path is parallel to the smoothed contours. When the West Dolores River established its path, downhill was toward the southwest. Subsequently, uplift off the east and southeast edge of the picture altered the topography, but the West Dolores River was entrenched and simple dug down deeper into the rising terrain.

In the second picture

(view area is southwest of the first picture) the East Dolores

River enters from the right edge to join the West Dolores

River. The combination forms the main Dolores River which

continues southwestward and then westward to McPhee Reservoir.

Lost Canyon Creek flows from east to west along the bottom

edge, and joins the Dolores River at the south end of McPhee

Reservoir. (The small town of Dolores is just to the right of

the south end of McPhee Reservoir.) The Dolores River then

turns abruptly toward the northwest and enters Dolores Canyon

in the upper left quadrant. Dolores Canyon continues northward

across the anticline with the river forming a canyon over

2,000 feet deep.

In the second picture

(view area is southwest of the first picture) the East Dolores

River enters from the right edge to join the West Dolores

River. The combination forms the main Dolores River which

continues southwestward and then westward to McPhee Reservoir.

Lost Canyon Creek flows from east to west along the bottom

edge, and joins the Dolores River at the south end of McPhee

Reservoir. (The small town of Dolores is just to the right of

the south end of McPhee Reservoir.) The Dolores River then

turns abruptly toward the northwest and enters Dolores Canyon

in the upper left quadrant. Dolores Canyon continues northward

across the anticline with the river forming a canyon over

2,000 feet deep.There is also a fault that runs from west-southwest to east-northeast through the center of McPhee Reservoir. Terrain to the southeast has been lifted several hundred feet above corresponding strata layers to the northwest.

Throughout the entire area shown in the picture, the Dolores River and its tributaries ignore current topography. Along the lower edge, Lost Canyon Creek is nearly parallel to current contours. The Dolores River from McPhee Reservoir to the northwest continues to flow parallel to the contour lines. If river systems followed today’s contours, they would flow southwestward toward the lower left corner. Obviously, some ancient river system obeyed an earlier topography, became entrenched, and continued these entrenched paths even though subsequent tectonic events changed the topography.

During the Eocene the ancestral San Juan River established a path across this area. It entered from the bottom edge (right of center) and exited at the top left. During the late Oligocene (and/or early Miocene) much of this area underwent regional uplift, which forced the San Juan River to find a new route further south in New Mexico. The upper portion of the current Dolores River (which was formerly just a tributary) was left as the sole owner of the old path from McPhee Reservoir downstream (up and left).

Lost Canyon Creek is another remnant of the ancestral San Juan drainage system. It was probably a local tributary to the ancestral San Juan.

This third picture

shows the continuation of the Dolores River where it cuts

through an anticline to form 2,000-ft. deep Dolores Canyon.

The ancestral San Juan River established this path some 50

million years ago. 50 million years ago, all drainage on the

western slope of the Rocky Mountains was from south to north

toward the Lake Uinta lowlands (Northeast Utah, Northwest

Colorado, and Southwest Wyoming), and the anticline did not

exist yet.

This third picture

shows the continuation of the Dolores River where it cuts

through an anticline to form 2,000-ft. deep Dolores Canyon.

The ancestral San Juan River established this path some 50

million years ago. 50 million years ago, all drainage on the

western slope of the Rocky Mountains was from south to north

toward the Lake Uinta lowlands (Northeast Utah, Northwest

Colorado, and Southwest Wyoming), and the anticline did not

exist yet.Some 20 to 30 million years ago, renewed uplifts from the La Plata Mountains southward forced the San Juan to relocate further south into New Mexico, but the upper Dolores River which was formerly just a tributary, inherited the entire route. Since then, the anticline has been uplifted, but the Dolores was entrenched and simply dug deeper to form Dolores Canyon. The zigzag path within Dolores Canyon is probably a remnant of another ancestral river (the ancestral Chaco River) that joined the ancestral San Juan before it too was truncated some 20 to 30 million years ago.

Return to the Image Index Page

Web page generated via Sea Monkey's Composer HTML editor

within a Linux Cinnamon Mint 18 operating system.

(Goodbye Microsoft)