Durango Bill's

Paleogeography (Historical Geology) Research

Appendix to the Evolution of the Colorado River and its Tributaries (Part 4)

Dolores River - Dolores to Gateway, CO

by

Bill Butler

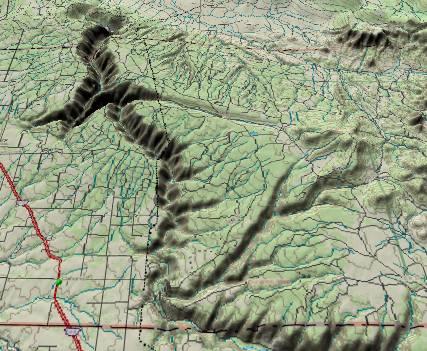

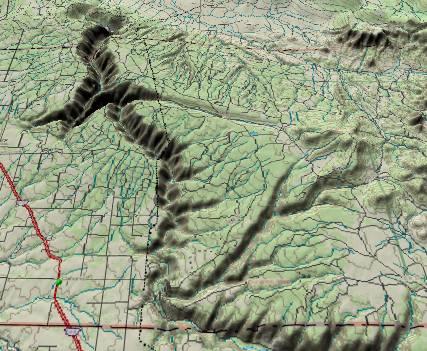

If the mechanics of

how the Colorado River got into the Grand Canyon looks a

little strange, the course of Dolores River from Dolores to

Delta CO appears to be out of touch with reality. (Please see

the Dolores

River 3-D map.) To the northwest of the town of Dolores,

the topographic (and stratigraphic) gradient tilts down to the

southwest. The logical route for the river would be a

southwestward “down the mountain” course that would form the

expected right angle to the contour lines. The wacko river

travels northwestward across this section and is thus parallel

to the contour lines.

Further downstream at

the boundary between Montezuma and Dolores Counties, there is

a large (50+ acres) gravel pit on the southwest rim of Dolores

Canyon. At some time in the past, the river actually occupied

this spot on the rim, which is now over 600 feet above the

present river. There is a gradient downhill from here to the

southwest. So naturally, our river ignores the downhill route

and turns due north with its path climbing diagonally over

1,000 vertical feet up the side of an anticline. (As measured

from the gravel pit on the rim to the top of the anticline.)

The river has actually dug a 2,000-foot deep canyon through

the anticline; but how and why did the river take this path in

the first place?

Further downstream at

the boundary between Montezuma and Dolores Counties, there is

a large (50+ acres) gravel pit on the southwest rim of Dolores

Canyon. At some time in the past, the river actually occupied

this spot on the rim, which is now over 600 feet above the

present river. There is a gradient downhill from here to the

southwest. So naturally, our river ignores the downhill route

and turns due north with its path climbing diagonally over

1,000 vertical feet up the side of an anticline. (As measured

from the gravel pit on the rim to the top of the anticline.)

The river has actually dug a 2,000-foot deep canyon through

the anticline; but how and why did the river take this path in

the first place?

The other side of the

anticline drops 2,500 feet down into Disappointment Valley.

This would be a perfect location for the river to use the

“straight down the mountain” route. However, the Dolores River

does not believe in the law of gravity and takes a diagonal

route – including two imbedded meanders, both of which have

short sections where the river turns directly back uphill. A

sane river would continue all the way down into the valley

where it could find an easy route. Just before reaching the

valley floor, the Dolores turns left to dig a cross-hill

canyon in the side of the valley en route to Slick Rock.

The other side of the

anticline drops 2,500 feet down into Disappointment Valley.

This would be a perfect location for the river to use the

“straight down the mountain” route. However, the Dolores River

does not believe in the law of gravity and takes a diagonal

route – including two imbedded meanders, both of which have

short sections where the river turns directly back uphill. A

sane river would continue all the way down into the valley

where it could find an easy route. Just before reaching the

valley floor, the Dolores turns left to dig a cross-hill

canyon in the side of the valley en route to Slick Rock.

From Slick Rock, the river travels a few miles through canyons to reach Big Gypsum Valley. Big Gypsum is a long, narrow northwest to southeast oriented valley. Instead of entering the valley via one of the ends, our loony river enters it from the southwest at the midpoint of the valley. At least the river begins to behave normally at this point and follows the valley to the northwest – for all of three miles. Although Big Gypsum Valley continues northwest for another six miles, the Dolores takes a dogleg to the right directly into the 1,000-foot high cliffs. For the next six linear miles, but more like 20 as the river flows, the Dolores follows a highly convoluted path through canyons in a path that roughly parallels Big Gypsum Valley but never finding it again.

A few more convoluted miles and the Dolores River wanders into Paradox Valley. (Understandably, whoever named it was also a little perplexed.) Paradox Valley is a 20-mile long northwest to southeast valley. A logical river might be expected to travel lengthwise down such a valley. Not our Dolores. It emerges from a 1,500-foot deep canyon at the midpoint on the southwest side of the valley, cuts straight across the valley toward the northeast (plus a meander or two), and immediately dives into another 1,500-foot deep canyon in the northeast wall of the valley.

For the remainder of its route to Gateway, the Dolores behaves more like a normal River. However, tributaries such as Roc (no “k”) and Salt Creeks continue the strange behavior.

All of the above

wanderings are completely illogical by today’s topography, but

we must remember the river (actually the ancestral San Juan

River) pioneered this path during the Eocene. Some 45 to 50

million years ago this was a simple downhill route from the

San Juan Basin (on the Colorado/New Mexico border) toward the

north where the old river emptied into the Lake Uinta

lowlands. This was when the river defined its course, started

the entrenchment process, and has maintained this entrenched

course ever since.

All of the above

wanderings are completely illogical by today’s topography, but

we must remember the river (actually the ancestral San Juan

River) pioneered this path during the Eocene. Some 45 to 50

million years ago this was a simple downhill route from the

San Juan Basin (on the Colorado/New Mexico border) toward the

north where the old river emptied into the Lake Uinta

lowlands. This was when the river defined its course, started

the entrenchment process, and has maintained this entrenched

course ever since.

The anticline had not risen yet during the Eocene. The northwest to southeast valleys did not exist either. The valleys were originally occupied with salt and gypsum deposits laid down 250 - 300 million years ago as evaporates from an ancient sea. These deposits were then covered by other sediments until they were exposed (or at least were near the surface) during the Miocene. At this point ground water dissolved the old evaporates, and the Dolores/Colorado River system carried them west to Utah’s deserts. Then, whatever was left of the overlying sediments (if anything) collapsed to form the valleys.

The current southwestward tilt in the strata from Dolores downstream to the anticline developed after the river was entrenched in this area. (The same southwestward tilt extends southeast of Dolores to include Lost Creek Canyon.)

The meanders in the river are a product of the silt flats that formed 5.4 million years ago as the whole Colorado River system backed up behind the rising Wasatch. Finally, the canyons were excavated after the Colorado River overflowed through the Kaibab and canyon cutting worked its way back upstream. More information about the evolution of the Dolores River follows.

Further downstream at

the boundary between Montezuma and Dolores Counties, there is

a large (50+ acres) gravel pit on the southwest rim of Dolores

Canyon. At some time in the past, the river actually occupied

this spot on the rim, which is now over 600 feet above the

present river. There is a gradient downhill from here to the

southwest. So naturally, our river ignores the downhill route

and turns due north with its path climbing diagonally over

1,000 vertical feet up the side of an anticline. (As measured

from the gravel pit on the rim to the top of the anticline.)

The river has actually dug a 2,000-foot deep canyon through

the anticline; but how and why did the river take this path in

the first place?

Further downstream at

the boundary between Montezuma and Dolores Counties, there is

a large (50+ acres) gravel pit on the southwest rim of Dolores

Canyon. At some time in the past, the river actually occupied

this spot on the rim, which is now over 600 feet above the

present river. There is a gradient downhill from here to the

southwest. So naturally, our river ignores the downhill route

and turns due north with its path climbing diagonally over

1,000 vertical feet up the side of an anticline. (As measured

from the gravel pit on the rim to the top of the anticline.)

The river has actually dug a 2,000-foot deep canyon through

the anticline; but how and why did the river take this path in

the first place? The other side of the

anticline drops 2,500 feet down into Disappointment Valley.

This would be a perfect location for the river to use the

“straight down the mountain” route. However, the Dolores River

does not believe in the law of gravity and takes a diagonal

route – including two imbedded meanders, both of which have

short sections where the river turns directly back uphill. A

sane river would continue all the way down into the valley

where it could find an easy route. Just before reaching the

valley floor, the Dolores turns left to dig a cross-hill

canyon in the side of the valley en route to Slick Rock.

The other side of the

anticline drops 2,500 feet down into Disappointment Valley.

This would be a perfect location for the river to use the

“straight down the mountain” route. However, the Dolores River

does not believe in the law of gravity and takes a diagonal

route – including two imbedded meanders, both of which have

short sections where the river turns directly back uphill. A

sane river would continue all the way down into the valley

where it could find an easy route. Just before reaching the

valley floor, the Dolores turns left to dig a cross-hill

canyon in the side of the valley en route to Slick Rock.From Slick Rock, the river travels a few miles through canyons to reach Big Gypsum Valley. Big Gypsum is a long, narrow northwest to southeast oriented valley. Instead of entering the valley via one of the ends, our loony river enters it from the southwest at the midpoint of the valley. At least the river begins to behave normally at this point and follows the valley to the northwest – for all of three miles. Although Big Gypsum Valley continues northwest for another six miles, the Dolores takes a dogleg to the right directly into the 1,000-foot high cliffs. For the next six linear miles, but more like 20 as the river flows, the Dolores follows a highly convoluted path through canyons in a path that roughly parallels Big Gypsum Valley but never finding it again.

A few more convoluted miles and the Dolores River wanders into Paradox Valley. (Understandably, whoever named it was also a little perplexed.) Paradox Valley is a 20-mile long northwest to southeast valley. A logical river might be expected to travel lengthwise down such a valley. Not our Dolores. It emerges from a 1,500-foot deep canyon at the midpoint on the southwest side of the valley, cuts straight across the valley toward the northeast (plus a meander or two), and immediately dives into another 1,500-foot deep canyon in the northeast wall of the valley.

For the remainder of its route to Gateway, the Dolores behaves more like a normal River. However, tributaries such as Roc (no “k”) and Salt Creeks continue the strange behavior.

All of the above

wanderings are completely illogical by today’s topography, but

we must remember the river (actually the ancestral San Juan

River) pioneered this path during the Eocene. Some 45 to 50

million years ago this was a simple downhill route from the

San Juan Basin (on the Colorado/New Mexico border) toward the

north where the old river emptied into the Lake Uinta

lowlands. This was when the river defined its course, started

the entrenchment process, and has maintained this entrenched

course ever since.

All of the above

wanderings are completely illogical by today’s topography, but

we must remember the river (actually the ancestral San Juan

River) pioneered this path during the Eocene. Some 45 to 50

million years ago this was a simple downhill route from the

San Juan Basin (on the Colorado/New Mexico border) toward the

north where the old river emptied into the Lake Uinta

lowlands. This was when the river defined its course, started

the entrenchment process, and has maintained this entrenched

course ever since.The anticline had not risen yet during the Eocene. The northwest to southeast valleys did not exist either. The valleys were originally occupied with salt and gypsum deposits laid down 250 - 300 million years ago as evaporates from an ancient sea. These deposits were then covered by other sediments until they were exposed (or at least were near the surface) during the Miocene. At this point ground water dissolved the old evaporates, and the Dolores/Colorado River system carried them west to Utah’s deserts. Then, whatever was left of the overlying sediments (if anything) collapsed to form the valleys.

The current southwestward tilt in the strata from Dolores downstream to the anticline developed after the river was entrenched in this area. (The same southwestward tilt extends southeast of Dolores to include Lost Creek Canyon.)

The meanders in the river are a product of the silt flats that formed 5.4 million years ago as the whole Colorado River system backed up behind the rising Wasatch. Finally, the canyons were excavated after the Colorado River overflowed through the Kaibab and canyon cutting worked its way back upstream. More information about the evolution of the Dolores River follows.

Return to La Plata Mountns.,

Upper Dolores River, & ancestral San Juan River (Part

3)

Continue to the Mancos Valley northwestward to Bishop & Summit Canyons (Part 5)

Return to the Main Appendix Page for the Evolution of the Colorado River

Web page generated via Sea Monkey's Composer HTML editor

within a Linux Cinnamon Mint 18 operating system.

(Goodbye Microsoft)

Continue to the Mancos Valley northwestward to Bishop & Summit Canyons (Part 5)

Return to the Main Appendix Page for the Evolution of the Colorado River

Web page generated via Sea Monkey's Composer HTML editor

within a Linux Cinnamon Mint 18 operating system.

(Goodbye Microsoft)